Ancient and Modern Sources of Hindu Law: A Concise Overview

This article discusses the ancient and modern sources of Hindu Law through a concise overview and depiction of the various origins of such laws.

This article discusses the ancient and modern sources of Hindu Law through a concise overview and depiction of the various origins of such laws. It also talks about the pattern of lineage in carrying these laws and the continuous-time frame, culture, and customs that have been essential factors in promoting and abolishing its inherent causes of it. Introduction Source of Law means “the roots of the law”, “cause of the law”, and “the things from which the laws have been taken”....

This article discusses the ancient and modern sources of Hindu Law through a concise overview and depiction of the various origins of such laws. It also talks about the pattern of lineage in carrying these laws and the continuous-time frame, culture, and customs that have been essential factors in promoting and abolishing its inherent causes of it.

Introduction

Source of Law means “the roots of the law”, “cause of the law”, and “the things from which the laws have been taken”. In the context of jurisprudence, the Sanskrit word Sindhu has been considered the origin of the word ‘Hindu’. A Hindu is an adherent of Hinduism.

The personal laws which governed and are even now governing the social life of Hindus (such as marriage and divorce, adoption, inheritance, minority and guardianship, family matters, etc.) are compiled in the form of Hindu Law. It is believed that Hindu law is a divine law.

It was revealed to the people by God through the Vedas. Various sages and ascetics have elaborated and refined the abstract concepts of life explained in the Vedas. The sources of Hindu law are ancient as well as modern sources.

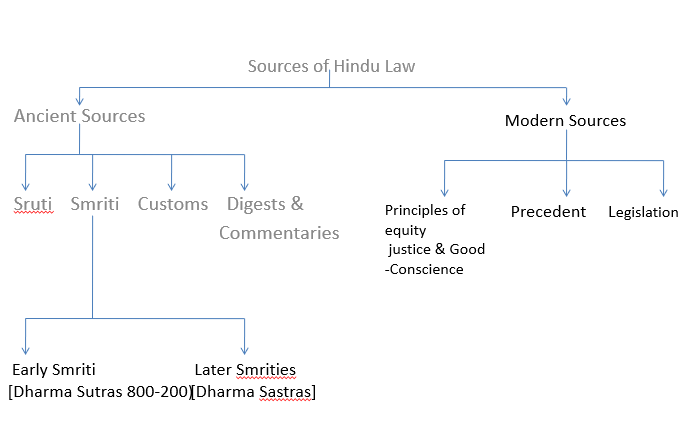

Representation of the various sources of Hindu Law

I. Ancient Sources of Hindu Law

A. Shruti[1]

The word is derived from the root “shru” which means “to hear”. In theory, it is the primary and paramount source of Hindu law and is believed to be the language of divine revelation through the sages. The material heard by people constitutes Shruti.

It is believed that Shruti contains the very words of the Deity. The Shruti comprise the four Vedas (Rig-Veda, Sum-Veda, Yajur-Veda and Atharva-Veda), the six Vedangas and eighteen Upanishads. Rigveda is first and foremost among the Shrutis for the knowledge of the law. It comprehensively deals with the duties of a king. Among Vedas, Rigveda distinguishes itself for its jurisprudential value.

It is believed that the Rishis and Munis had reached the height of spirituality, where they revealed their knowledge of Vedas. Vedas primarily contain theories about sacrifices, rituals, and customs. Since Vedas had a divine origin, the society was governed as per the theories given in them, and they are considered to be the fundamental source of Hindu Vedangas.

The Upanishads are known as Vedantas or concluding portions of the Vedas and embody the highest principles of the Hindu religion. Vedas do refer to certain rights and duties, forms of marriage, the requirement of a son, exclusion of women from the inheritance, and partition, but these are not very clear-cut laws.

B. Smriti[2]

The word Smriti is derived from the root “smri” meaning “to remember”. Traditionally, Smritis contain those portions of the Shrutis that the sages forgot in their original form and the idea whereby they wrote in their own language with the help of their memory.

According to jurisprudence, the words remembered are those which were heard but were forgotten. Through a series of meditations, the words were recollected by the Rishis.

So, the basis of the Smritis is Shrutis but they are human works. The rules laid down in Smritis can be divided into three categories viz. Achar (relating to morality), Vyavahar (signifying procedural and substantive rules which the King or the State applied for settling disputes in the adjudication of justice) and Prayaschit (signifying the penal provision for the commission of a wrong).

There are two kinds of Smritis. Their subject matter is almost the same.

1. Dharmasutras (Early smritis)

Dharmasutras are written in prose, in short maxims (Sutras). The Dharmasutras were written from 800 to 200 BC. They were mostly written in prose form but also contained verses. It is clear that they were meant to be training manuals of sages for teaching students.

They incorporate the teachings of Vedas with local customs. They generally bear the names of their authors and sometimes also indicate the shakhas to which they belong. Some of the important sages whose Dharmasutras are known are: Gautama, Baudhayan, Apastamba, Harita, Vashistha, and Vishnu. They explain the duties of men in various relationships.

- Gautama – He belonged to Samveda school and deals exclusively with legal and religious matters. He talks about inheritance, partition, and stridhan.

- Baudhayan – He belonged to the Krishna Yajurveda school and was probably from Andhra Pradesh. He talks about marriage, sonship, and inheritance. He also refers to various customs of his region, such as marriage to maternal uncle’s daughter.

- Apastamba – His sutra is most well-preserved. He also belonged to Krishna Yajurveda school from Andhra Pradesh. His language is very clear and forceful. He rejected Prajapatya's marriage.

- Vashistha – He was from North India and followed the Rigveda school. He recognized remarriage of virgin widows.

2. Dharmashastras (Later smritis)[3]

Dharmashastras are composed in poetry (Shlokas). Dharmashastras were mostly in metrical verses and were based on Dharmasutras. However, they were a lot more systematic and clearer. However, occasionally, we find Shlokas in Dharmasutras and Sutras in the Dharmashastras.

“Smriti” means “what is remembered”. With Smritis, a systematic study and teaching of Vedas started. Many sages, from time to time, have written down the concepts given in Vedas. So, it can be said that Smritis are a written memoir of the knowledge of the sages.

Immediately after the Vedic period, a need for the regulation of society arose. Thus, the study of Vedas and the incorporation of local culture and customs became important. It is believed that many Smritis were composed in this period, and some were reduced into writing. However, not all are known.

From the history above, the fact which becomes obvious is that the Vedas were divine laws, while the Smritis were more secular laws dealing with morality and religion. The Smriti was accepted as statements of laws, and they became an effective source of Hindu Law. The laws laid down in Smritis included the law on morality, procedural and substantive rules applied in the adjudication of disputes, and penal provisions meted out as punishments on wrongdoers.

Smritis are the foundation of Hindu Law. Juristically they occupy an important position. They contain a vivid exposition of all such laws which are generally relevant for regulating the conduct of man in various areas in modern times also. The rules incorporated in these Dharmashastras bear distinct reflections of the changing needs of society.

C. Custom

Customs are a principal source, and their position is next to the Shrutis and Smritis, but usage of custom prevails over the Smritis. It is superior to written law.

Custom is regarded as the third source of Hindu law. From the earliest period custom (‘Achara’) is regarded as the highest ‘dharma’. As defined by the Judicial Committee, custom signifies a rule which, in a particular family or in a particular class or district has from long usage obtained the force of law.

Most of the Hindu law is based on customs and practices followed by the people all across the country. Even smritis have given importance to customs. They have held customs as transcendent law and have advised the Kings to give decisions based on customs after due religious consideration.

Customs are of four types:

- Local Customs: These are the customs that are followed in a given geographical area. In the case of Subbane v. Nawab[4], Privy Council observed that a custom gets it force due to the fact that due to its observation for a long time in a locality, it has obtained the force of law.

- Family Customs: These are the customs that are followed by a family for a long time. These are applicable to families where ever they live. They can be more easily abandoned than other customs. In the case of Soorendranath v. Heeramonie and Bikal v Manjura[5], Privy Council observed that customs followed by a family have long been recognized as Hindu law.

- Caste and Community Customs: These are the customs that are followed by a particular caste or community. It is binding on the members of that community or caste. By far, this is one of the most important sources of laws. For example, most of the law in Punjab belongs to this type. The custom of marrying a brother’s widow among certain communities is also of this type.

- Guild Customs: These are the customs that are followed by traders.

Requirements for a valid custom[6]

- Ancient: Ideally, a custom is valid if it has been followed for hundreds of years. There is no definition of ancientness. However, 40 years have been determined to be ancient enough.

- Continuous: It is important that the custom is being followed continuously and has not been abandoned. Thus, a custom maybe 400 years old, but once abandoned, it cannot be revived.

- Reasonable: There must be some reasonableness and fairness in the custom.

- Not against morality: It should not be morally wrong or repugnant. For example, a custom to marry one’s granddaughter has been held invalid. In the case of Chitty v. Chitty[7], a custom that permits divorce by mutual consent and by payment of expenses of marriage by one party to another was held to be not immoral. In the case of Gopikrishna v. Mst Jagoo,[8] a custom that dissolves the marriage and permits a wife to remarry upon abandonment and desertion of the husband was held to be not immoral.

- Not against any law: If a custom is against any statutory law, it is invalid. Codification of Hindu law has abrogated most of the customs except the ones that are expressly saved. In the case of Prakash v. Parmeshwari[9], it was held that law means statutory law.

- Certainty: The custom has to be clearly defined. It cannot be vague and confusing.

- Consistency: There should be consistency between customs. Two customs that have opposing viewpoints cannot be considered valid.

D. Digests and Commentaries[10]

Commentaries (Tika or Bhashya) and Digests (Nibandhs) covered a period of more than a thousand years from the 7th century to 1800 A.D. In the first part of the period, most of the commentaries were written on the Smritis but in the later period, the works were in the nature of digests containing a synthesis of the various Smritis and explaining and reconciling the various contradictions.

After 200 AD, most of the work was done only on the existing material given in Smritis. The work done to explain a particular smriti is called a commentary. Commentaries were composed in the period immediately after 200 AD. Digests were mainly written after that and incorporated and explained material from all the Smritis. In the evolution of Hindu legal and social institutions, according to N.R. Raghavachariar, “Commentaries and Digests have played an important part and have in effect superseded the Smritis in large measure.”

Some of the commentaries were, Manubhashya, Manutika, and Mitakshara. While the most important digest is Jimutvahan’s Dayabhaga which is applicable in the Bengal and Orissa area.

“Mitakshara” literally means “New Word” and is the paramount source of law in all of India. It is also considered important in Bengal and Orissa where it relents only where it differs from Dayabhaga. It is a very exhaustive treatise of law and incorporates and irons out contradictions existing in Smritis.

The Dayabhaga and Mitakshara are the two major schools of Hindu law. The Dayabhaga School of law is based on the commentaries of Jimutvahana (author of Dayabhaga which is the digest of all Codes) and the Mitakshara is based on the commentaries written by Vijnaneshwar on the Code of Yajnavalkya.

The basic objective of these texts was to gather the scattered material available in preceding texts and present a unified view for the benefit of society. Thus, digests were very logical and to the point in their approach. Various digests have been composed from 700 to 1700 AD.

II. Modern sources of law

A. Principles of equity, justice and good conscience[11]

Our judicial system greatly relies on being impartial. True justice can only be delivered through equity and good conscience. Occasionally it might happen that a dispute comes before a Court that cannot be settled by the application of any existing rule in any of the sources available.

Such a situation may be rare, but it is possible because not every kind of fact or situation that arises can have a corresponding law governing it.

The Courts cannot refuse to settle the dispute in the absence of law and they are under an obligation to decide such a case also. For determining such cases, the Courts rely upon the basic values, norms, and standards of fair play and propriety.

These are known as principles of justice, equity, and good conscience. They may also be termed Natural law. This principle in our country had enjoyed the status of a source of law since the 18th century when the British administration made it clear that in the absence of a rule, the above principle shall be applied.

In the case of Kanchava v. Girimalappa (1924) 51 IA 368, (before the passing of the Hindu Succession Act, 1956), it was laid down by the Privy Council that the murderer was disqualified from inheriting the property of the victim. The rule of English Law was applied to Hindus on the grounds of justice, equity, and good conscience, and this was statutorily recognized in the Hindu Succession Act of 1956.

B. Precedent

The doctrine of stare decisis started in India under British rule. All cases are now recorded, and new cases are decided based on existing case laws. After the establishment of British rule, the hierarchy of Courts was established.

The doctrine of precedent based on the principle of treating cases alike was established. Today, the judgment of the SC is binding on all courts across India and the judgment of the HC is binding on all courts in that state, except where they have been modified or altered by the Supreme Court, whose decisions are binding on all the Courts except for itself.

C. Legislations

Legislations are Acts of Parliament which have been playing a profound role in the formation of Hindu law. Legislation has the effect of reforming the law and, in certain respects, has superseded the textual law. After India achieved independence, some important aspects of Hindu Law have been codified. A few examples of important Statutes are The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, The Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956, The Hindu Succession Act, 1956, The Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956, etc.

After codification, any point dealt with by the codified law is final. The enactment overrides all prior law, whether based on custom or otherwise, unless an express saving is provided for in the enactment itself. In matters not specifically covered by the codified law, the old textual law contains to have application.

Conclusion

Hindu law does not bear a very modern outlook on society. There are many areas where the Hindu law needs to upgrade itself. For example, the irretrievable breakdown theory as a valid ground for divorce is still not recognised under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. Even the Supreme Court has expressed its concern about this.

Most of the ancient sources of Hindu law are written in Sanskrit, and it is well known that in the present times, there is a dearth of Sanskrit scholars. There is hardly any importance left of the ancient sources since the time the modern sources have emerged and been followed.

It can be said that proper codification of Hindu law without room for ambiguity is the need of the hour. It can be said that where the present sources of Hindu law are uninviting, the Legislature could look into sources and customs of other religions and incorporate them into Hindu law if it caters to the society's need and meets the test of time.

[1] J.R. Gharpare, Hindu Law, 1st edition (1905) available here

[2] Keshav Jha, Sources of Hindu Law: A Comprehensive View, International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews (2019) available here

[3] J Duncan Derrett, Introduction to Modern Hindu Law, The American Journal of Comparative Law (1968), available here

[4] (1941) 43 BOMLR 432

[5] AIR 1973 Pat 208

[6] Section 3(a), Hindu Marriage Act 1955

[7] 118 N.C. 647

[8] (1936) 38 BOMLR 751

[9] AIR 1987 P H 37

[10] Supra Note 2

[11] Kalyani Ramnath, Justice in her Infinite Variety, India in the Shadows of the Empire: A Legal and Political History, Manupatra Articles (2010) available here

Nitya Bansal

She is a B.A.LLB (H) student at National Law University Delhi. She enjoys legal research and drafting, and is currently associated with the Centre for Communication Governance as a Research Assistant.